10. Threads

In the world of system programming, threads play a pivotal role in achieving concurrency and efficient resource utilization.

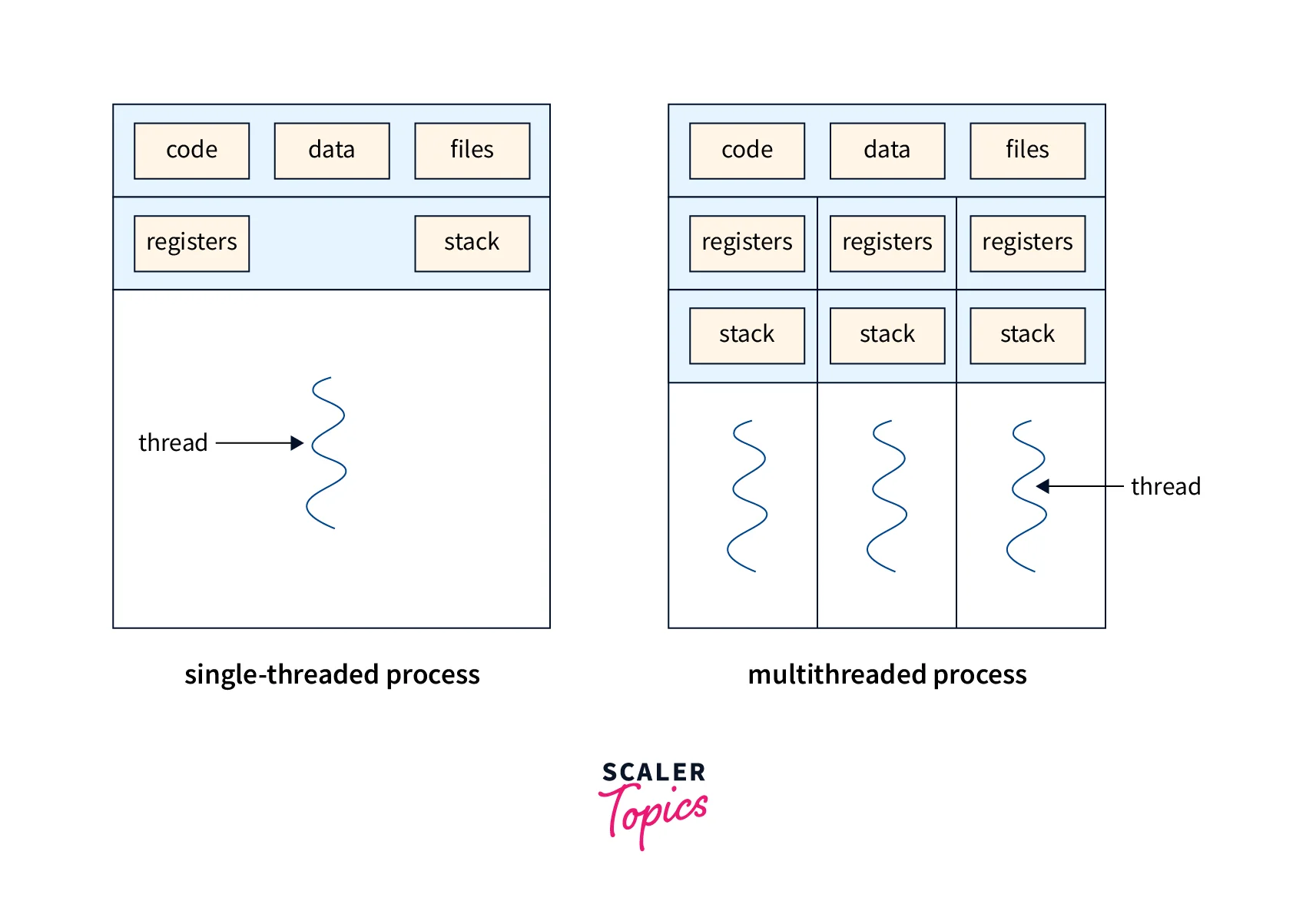

A thread is the smallest unit of execution within a process. Unlike processes, which have separate memory spaces, threads within the same process share:

- Code

- Data segment

- Heap memory

- Open files and sockets

However, each thread has its own:

- Stack

- Register set

- Program counter (PC)

This shared memory model makes threads faster to create and manage compared to processes but requires careful synchronization to avoid race conditions.

Threading Models in Linux

In Linux, threads are implemented using the NPTL (Native POSIX Thread Library) (<pthread.h>), which uses the clone() system call under the hood. The two main threading models are:

- User-Level Threads: Managed by user-level libraries without kernel awareness. They are lightweight but can block the entire process if one thread performs a blocking operation.

- Kernel-Level Threads: Managed directly by the operating system kernel, allowing better scheduling and management. The kernel is aware of all threads and can schedule them independently.

Linux uses a 1:1 threading model, where each user thread maps directly to a kernel thread.

- pthread is a standard set of thread management functions used to create, synchronize, and manage threads.

- The pthread library provides functions for thread creation, synchronization, and termination, as well as for handling attributes like priority, stack size, and detachability.

Key Functions

pthread_create()– Creates a new thread.pthread_join()– Waits for a thread to terminate.pthread_exit()– Terminates the calling thread.pthread_detach()– Allows a thread to run independently (no need forjoin).

Creating Threads in Linux

The pthread_create() function is used to create a new thread:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void *thread_function(void *arg) {

printf("Inside the thread!\n");

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread_id;

int ret = pthread_create(&thread_id, NULL, thread_function, NULL);

if (ret != 0) {

perror("Thread creation failed");

return 1;

}

pthread_join(thread_id, NULL); // Wait for the thread to finish

printf("Thread execution complete.\n");

return 0;

}

Thread Synchronization

In multithreaded applications, synchronization mechanisms are essential to manage access to shared resources. Common techniques include:

- Mutexes: Used to ensure mutual exclusion when accessing shared data.

- Condition Variables: Allow threads to wait for certain conditions to be met before proceeding.

- Barriers: Synchronize multiple threads at specific points in execution, ensuring that all threads reach a certain point before any can proceed.

Refer:

Info

When we talk about a process in traditional Unix/Linux terminology, we’re talking about:

An independent execution unit with:

- Its own address space (virtual memory).

- Own set of file descriptors.

- One execution flow: A single program counter (PC), single stack, and registers.

Such a process naturally has only one thread of execution.

Thus, a “normal process” (without explicitly creating threads) is effectively a single-threaded process.

When a program starts:

- It always begins with one thread of execution.

- This initial thread is often called the main thread.

Difference Between exit() and pthread_exit()

| Feature | exit() | pthread_exit() |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Terminates the entire process | Terminates calling thread only |

| Effect on Other Threads | Terminates all threads immediately | Other threads continue running normally |

| Resource Cleanup | Cleans up process resources; runs atexit() handlers | Cleans up resources of the thread only |

| Return Value Use | Returns status code to OS (process exit code) | Thread return value (retrievable via pthread_join()) |

| Typical Use Case | Process termination (e.g., on fatal error) | Thread termination in multi-threaded programs |

Thread ID

Every thread—whether in a single-threaded or multi-threaded process—has a unique Thread ID (TID). It’s crucial for managing threads correctly.

A Thread ID (TID) uniquely identifies a thread within the system.

In Linux:

- Every thread is represented by a kernel-level task (using

clone()internally). Each thread has:

- A unique Thread ID (TID).

- A Process ID (PID), often the same as TID in single-threaded programs.

Warning

pthread_t is not guaranteed to be an integer or TID—it’s an opaque handle in POSIX (though many systems internally use integers).

Following example will clear it -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

void* thread_func(void* arg) {

printf("Thread: pthread_t = %lu, TID = %ld, PID = %d\n",

pthread_self(), syscall(SYS_gettid), getpid());

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread;

pthread_create(&thread, NULL, thread_func, NULL);

printf("Main thread: pthread_t = %lu, TID = %ld, PID = %d\n",

pthread_self(), syscall(SYS_gettid), getpid());

pthread_join(thread, NULL);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

$ ./tid

Main thread: pthread_t = 140304230987584, TID = 295124, PID = 295124

Thread: pthread_t = 140304227235392, TID = 295125, PID = 295124

You’ll notice that the main thread’s TID is the same as the process’s PID. This is because the main thread represents the initial thread of the process, and it shares the same ID as the process itself. In short, it’s the initial thread that starts when the process begins.

Race Condition

When working with threads, one of the most common and dangerous problems is a race condition. A race condition occurs when multiple threads access shared data simultaneously, leading to unpredictable and incorrect behavior. I’ll what race conditions are, why they happen, and how to prevent them.

A race condition happens when:

- Two or more threads access shared data at the same time.

- At least one thread modifies the data.

- The final result depends on the timing of thread execution.

Since the OS scheduler can interrupt threads at any point, the order of execution is non-deterministic, leading to inconsistent results.

Example of a Race Condition

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int counter = 0;

void *increment_counter(void *arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

counter++; // Non-atomic operation (read-modify-write)

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread1, thread2;

pthread_create(&thread1, NULL, increment_counter, NULL);

pthread_create(&thread2, NULL, increment_counter, NULL);

pthread_join(thread1, NULL);

pthread_join(thread2, NULL);

printf("Final counter value: %d\n", counter); // Expected: 200000, but often less!

return 0;

}

On compiling and running -

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ tmp ./race

Final counter value: 136530

$ tmp ./race

Final counter value: 166144

$ tmp ./race

Final counter value: 107189

Why does this fail?

counter++is not atomic (it involves read → modify → write).- If two threads read

counterat the same time, they may overwrite each other’s updates.