6. Virtual Memory of Process

In the early days of computing, programs had direct access to physical memory (RAM). This worked when computers ran one program at a time. But as systems became more complex and started supporting multitasking, this approach hit several critical roadblocks:

The Problems with Direct Physical Memory Access -

1. Limited Physical Memory (RAM) Constraints

- Programs could only use the available RAM.

- Larger programs couldn’t run if RAM was insufficient.

- No way to “swap” unused data to disk to free up space.

2. No Memory Protection (Security & Stability Issues)

- One program could accidentally (or maliciously) overwrite another program’s memory.

- A bug in one application could crash the entire system.

- No isolation between processes → unreliable multitasking.

3. Fragmentation Problems

- External Fragmentation: Free memory became scattered in small chunks over time, making it hard to allocate contiguous blocks for large programs.

- Internal Fragmentation: Fixed-size memory partitions wasted space if a program didn’t fully use its allocated block.

4. Inflexible Memory Management

- Programs had to be loaded entirely into RAM, even if only a small part was needed.

- No support for demand paging (loading only required sections).

6. Difficulty in Sharing Memory Between Processes

- Without virtual memory, sharing code (e.g., libraries) between processes required manual memory management, increasing complexity.

- No copy-on-write optimizations, leading to unnecessary duplication.

Virtual Memory allows processes to use more memory than is physically available on the system. It abstracts the physical memory (RAM) and provides each process with its own private address space, enhancing multitasking capabilities and process isolation.

Virtual Address Space

Virtual Address Space (VAS) is the range of memory addresses that a process can use, provided by the operating system through virtual memory abstraction. Unlike physical memory (RAM), which is limited by hardware, VAS allows each process to operate as if it has its own dedicated, contiguous memory space—even if the actual physical memory is shared or fragmented.

Each process operates within its own virtual address space, which can exceed the actual physical memory available. This space is managed by the operating system and includes both RAM and disk-based swap space.

Each process has its own private VAS, preventing unauthorized access to other processes’ memory. A process cannot directly access physical memory; all addresses are translated via the MMU (Memory Management Unit). VAS can be much larger than available RAM (e.g., 32-bit systems: 4GB, 64-bit: 16 exabytes).

A typical VAS is divided into segments:

- Code (Text): Executable instructions (read-only).

- Data: Global and static variables.

- Heap: Dynamically allocated memory (grows upwards).

- Stack: Local variables, function calls (grows downwards).

- Shared Libraries: Memory-mapped system libraries.

- Kernel Space: Reserved for OS (inaccessible to user processes).

Example (32-bit Linux Process)

0xFFFFFFFF (4GB) ┌───────────────────────┐

│ Kernel Space │

0xC0000000 (3GB) ├───────────────────────┤

│ Stack │ (Grows ↓)

├───────────────────────┤

│ Shared Libs │

├───────────────────────┤

│ Heap │ (Grows ↑)

├───────────────────────┤

│ Data │

├───────────────────────┤

│ Code (Text) │

0x00000000 (0GB) └───────────────────────┘

The OS uses virtual memory (backed by paging and swapping) to move inactive memory pages from RAM to disk (e.g., into a pagefile or swap partition).

Paging

Linux uses a technique called paging to manage memory. This involves dividing the virtual memory into fixed-size pages, which can be loaded into or swapped out of physical memory as needed. When a process requires more memory than is available, less frequently used pages are moved to disk (swap space) to free up RAM for active processes.

Swapping vs. Paging:

- Swapping: Involves moving entire processes from RAM to disk when physical memory is full.

- Paging: Only specific pages of memory are moved to disk, allowing for more efficient use of memory resources.

Techniques Used in Linux Virtual Memory Management

- Copy-on-Write (COW): This technique allows multiple processes to share the same physical memory pages until one process attempts to modify a page. At that point, a copy of the page is made for the modifying process, conserving memory usage when processes share data.

- Demand Paging: Pages are only loaded into RAM when a process explicitly accesses them. This reduces the initial load time and conserves memory by not loading unnecessary pages.

- Page Aging: The Linux kernel keeps track of page usage over time. Pages that are not accessed frequently can be swapped out to disk, while more active pages remain in RAM.

Memory Management Components

1. Memory Management Unit (MMU)

Function: Hardware component that performs virtual-to-physical address translation

Responsibilities:

- Enables access to both RAM and swap space

- Manages memory protection through page tables

- Handles translation lookaside buffer (TLB) operations

2. Page Fault Handler

Trigger: Activated when a process accesses a page not in physical memory

Process Flow:

- Page fault exception occurs

OS determines fault type:

- Valid access (page in swap space)

- First access (zero-fill page)

- Invalid access (protection fault)

Appropriate action taken:

- Load from disk (if swapped out)

- Allocate new page (first access)

- Terminate process (invalid access)

3. Memory Pager (Swapper)

Primary Role: Manages page replacement between RAM and disk

Key Functions:

- Implements page replacement algorithms (LRU, FIFO, Clock)

- Maintains working sets of active processes

- Balances memory pressure across the system

To translate a virtual address to a physical address in Linux, the system relies on a combination of hardware and software mechanisms, primarily involving the Memory Management Unit (MMU) and page tables. Here’s a detailed overview of this process:

Translation Process

1. Virtual Address Structure

A virtual address is typically divided into two parts:

- Virtual Page Number (VPN): Identifies the page in the virtual address space

- Offset: Indicates the specific location within that page

For instance, in a 32-bit architecture with 4KB pages, the virtual address can be structured as follows:

- The upper bits correspond to the VPN

- The lower bits represent the offset within the page

2. Page Tables

The operating system maintains a set of data structures known as page tables. Each process has its own page table that maps virtual pages to physical frames in memory. The translation involves several levels of page tables:

- Page Global Directory (PGD)

- Page Upper Directory (PUD)

- Page Middle Directory (PMD)

- Page Table Entry (PTE)

Each level of the table is indexed using parts of the VPN, allowing for hierarchical lookup.

Example: x86-64 uses 4-level paging (PGD→PUD→PMD→PTE) consuming 9 bits of VPN per level.

The following diagram depicts the layout of the page table for x86-64:

Source Oreilly

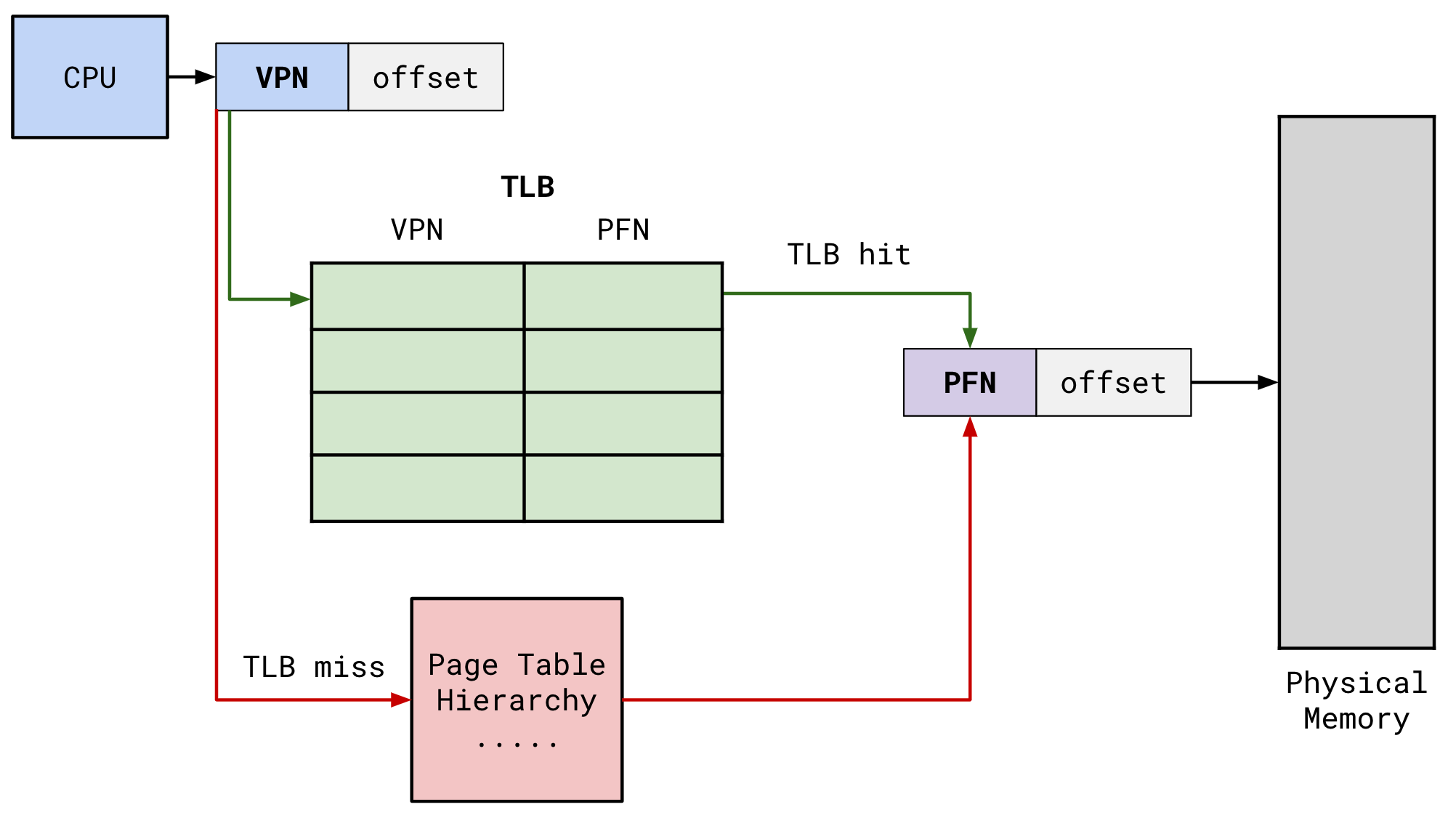

3. Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

To speed up the translation process, the MMU uses a cache called the TLB, which stores recent translations of virtual addresses to physical addresses. When a virtual address is accessed:

- The MMU first checks the TLB for a matching entry

- If found (TLB hit), it retrieves the physical address directly

- If not found (TLB miss), it proceeds to walk through the page tables

Source cs4118.github.io

- Walking the Page Tables: If a TLB miss occurs, the system must walk through the page tables:

- Start from the PGD and use part of the VPN to index into it.

- Continue down to PUD, PMD, and finally PTE, checking for valid entries at each level.

- If a valid PTE is found, it contains the frame number corresponding to the physical address.

- Calculating Physical Address: Once the correct PTE is located:

- The physical frame number (PFN) is extracted from it.

- The physical address is calculated by combining this PFN with the original offset from the virtual address.

The formula for calculating the physical address is:

Physical Address=(PFN<<PAGE SHIFT)∣Offset

Example Code Snippet

In kernel space, you can translate a virtual address to a physical address using code similar to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

unsigned long get_physical_address(void *virtual_address) {

struct mm_struct *mm = current->mm;

pgd_t *pgd = pgd_offset(mm, (unsigned long)virtual_address);

pud_t *pud = pud_offset(pgd, (unsigned long)virtual_address);

pmd_t *pmd = pmd_offset(pud, (unsigned long)virtual_address);

pte_t *pte = pte_offset_map(pmd, (unsigned long)virtual_address);

if (!pte_none(*pte)) {

return (pte_val(*pte) & PAGE_MASK) | ((unsigned long)virtual_address & ~PAGE_MASK);

}

return 0; // Invalid address

}

User-Space Access

In user space, you can access mappings using special files in /proc:

/proc/<pid>/maps: Lists memory mappings for a process./proc/<pid>/pagemap: Provides information about each mapped page, including whether it is present in RAM and its corresponding physical address if available.