5. Introduction to Process

Process

A process is an executing instance of a program. When you run a program, it creates a process that contains the program’s code, data, and resources. Each process has its own memory space, execution state, and system resources. fork() creates a new process by duplicating the calling process. The new process is referred to as the child process. The calling process is referred to as the parent process. The child process and the parent process run in separate memory spaces. At the time of fork() both memory spaces have the same content. Memory writes, file mappings (mmap(2)), and unmappings (munmap(2)) performed by one of the processes do not affect the other.

The child has its own unique process ID. The child’s parent process ID is the same as the parent’s process ID.

Creating a Process

In UNIX-like systems, processes are created using the fork() system call. fork() creates a new child process that is a duplicate of the calling (parent) process.

1

2

#include <unistd.h>

pid_t fork(void);

fork() returns:

- 0 in the child process.

- The PID (Process ID) of the child process in the parent process.

- -1 on error.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("[+] PID %d\n", getpid());

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid == -1) {

perror("fork");

return 1;

}

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Hello from child process! (PID: %d)\n", getpid());

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Hello from parent process! (PID: %d)\n", getpid());

}

return 0;

}

Both processes continue executing from the point of the fork() call.

Process ID (PID): Every process in a UNIX-like system has a unique identifier called the Process ID (PID). You can obtain the PID of the current process using getpid(). getppid() returns the process ID of the parent of the calling process.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

pid_t pid = getpid();

pid_t ppid = getppid();

printf("My PID is: %d\n", pid);

printf("My PPID is: %d\n", ppid);

return 0;

}

pid_t is a type used for storing process IDs, process group IDs, and session IDs. It is a signed integer type. uid_t is a type used to hold user IDs. It is an integer type. gid_t is a type used to hold group IDs. It is an integer type. id_t is a type used to hold a general identifier. It is an integer type that can be used to contain a pid_t, uid_t, or gid_t.

On running we can see that the ppid of the process matches to the pid of bash which is child of gnome-terminal and which is child of systemd

Systemd is a comprehensive system and service manager for Linux operating systems, designed to streamline the initialization process and manage system resources effectively. It has become the default init system for many major Linux distributions, replacing older systems like SysVinit. Systemd is often referred to as the “mother of all processes” in Linux because it is the first process started during the boot sequence and serves as the parent for all other processes.

PID 1: Systemd runs as the first process on boot (PID 1), managing all other processes. It initializes the user space and maintains services throughout the system’s uptime. Systemd offers aggressive parallelization capabilities, allowing multiple services to start simultaneously, which significantly speeds up boot times compared to traditional sequential startup methods. In systemd, a unit refers to any resource that the system can manage, including services, sockets, devices, mounts, and more. Each unit is defined in a unit file that specifies how it should behave.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ ./ppid

My PID is: 5374

My PPID is: 4468

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

4468 pts/0 00:00:01 bash

5393 pts/0 00:00:00 ps

Program Loading and Initialization When a C program is executed, the operating system loader is responsible for loading the executable file into memory. This includes copying the code and data segments from the executable file to their respective locations in memory.

The loader jumps to the program’s entry point, which is typically defined as the _start function. This function is not part of your source code but is provided by the C runtime library (libc) and is written in assembly language.

The _start function initializes the execution environment. It sets up necessary registers and prepares arguments for the next function call. This includes setting up the stack and preparing command-line arguments (argc, argv) for main.

After initialization, _start calls __libc_start_main, which is responsible for further setting up the C runtime environment.

Once all preparations are complete, __libc_start_main calls your program’s main function. At this point, your code begins executing.

The main function executes according to its defined logic.

After main finishes executing, it returns a value (typically 0 for success). This return value is passed back to __libc_start_main, which then performs any necessary cleanup operations before returning control back to the operating system.

Process Termination: A process can terminate in several ways:

- Calling exit(status) to terminate with a specific status code.

- Reaching the end of the main function.

- Receiving a signal that causes termination (SIGTERM, SIGKILL, etc.).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

printf("Before exit()\n");

exit(0); // Terminate the process with status code 0

printf("This line will not be reached\n");

return 0;

}

But if we use fork():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("Before exit()\n");

exit(0); // Terminate the process with status code 0

printf("This line will not be reached\n");

return 0;

}

Process Synchronization:

Processes may need to synchronize their execution to avoid race conditions. This is often done using synchronization primitives like semaphores, mutexes, and condition variables.

You can refer this

In Linux and Unix-like systems, the process with PID (Process ID) 0 is a special process known as the “swapper” or “scheduler” process. This process is not a regular user-space process, and it serves as the ancestor of all processes. The swapper/scheduler process is not a real user-space process. It is created by the kernel during system boot and is part of the kernel’s process table. It is given PID 0, making it the ancestor of all other processes on the system. All other processes are descendants of this process through a series of fork() and exec() calls. Unlike regular processes that have user-space code associated with them, the swapper/scheduler process does not have an executable file or user-space code. The swapper/scheduler process operates entirely in kernel space, managing system resources and handling core scheduling functions. During system boot, the kernel creates the swapper/scheduler process (PID 0). Once the init process (PID 1) is started, the kernel hands over control to the init process, and the swapper/scheduler process becomes essentially idle. It remains in the process table for the entire lifetime of the system, handling critical kernel-level tasks. While PID 0 is a special process and not a user-space process, you won’t typically see it in the output of commands like ps or top because these commands usually only show user-space processes.

In Linux, at system startup, the first process that is executed is called the init process. The init process has process ID (PID) 1 and is responsible for starting and managing all other processes on the system. It’s essentially the parent or grandparent of all other processes.

The Init Process The init process is special because it’s the first user-space process started by the kernel during the booting process. Its primary responsibility is to bring the system into a usable state. This includes:

- Starting system services

- Process Management

- Runlevel Management

Evolution: From SysVinit to systemd

Historically, Linux systems used the SysVinit system, where the init process was controlled by a series of scripts in /etc/init.d/. These scripts defined how services were started, stopped, and managed.

However, modern Linux distributions have largely transitioned to using systemd as the init system. systemd is more sophisticated and provides advanced features like dependency-based service management, parallel startup of services, socket activation, and more.

You can view the processes running on your Linux system using various commands like ps, top, htop, or pgrep.

The /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max file in Linux contains the maximum value that the kernel will allow for PIDs (Process IDs). This value represents the upper limit for the PID numbers that can be assigned to processes on the system. The value you see in /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max is often one greater than the actual maximum PID allowed. This is because the maximum PID is inclusive of 0 and the maximum PID value specified in pid_max. So, if pid_max is set to N, the valid PID range is from 0 to N. This means there are N+1 possible PIDs, hence the value you see in /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max is N+1. For example, if you see 4194304 in /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max, the valid PID range is from 0 to 4194303, which includes 4194304 possible PIDs.

To see every process on the system using standard syntax:

1

ps -ef

To print a process tree:

1

ps -ejH

But my favourite tool is pstree and procs :)

Parent Process ID (PPID): The Parent Process ID (PPID) in Linux and Unix-like operating systems is the process ID (PID) of the parent process that created the current process. Every process, except for the init process (PID 1), has a PPID. The PPID is used to establish a parent-child relationship between processes in the system’s process tree.

In a C program, you can obtain the PPID of the current process using the getppid() function. This function is declared in

1

2

#include <unistd.h>

pid_t getppid(void);

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

pid_t parent_pid = getppid();

printf("Parent Process ID (PPID): %d\n", parent_pid);

return 0;

}

1

2

3

$ gcc ppid.c -o ppid

$ ./ppid

Parent Process ID (PPID): 15920

1

pstree -p # Displays a tree diagram of processes, showing the parent-child relationships.

Consider a scenario where a parent process creates a child process. The child process inherits the PPID of the parent.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

pid_t child_pid = fork();

if (child_pid == -1) {

perror("fork");

return 1;

}

if (child_pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Child Process: PID=%d, PPID=%d\n", getpid(), getppid());

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Parent Process: PID=%d, PPID=%d\n", getpid(), getppid());

}

return 0;

}

Process States

In Unix-like operating systems, processes can exist in different states as they execute and interact with the system. Understanding these states is crucial for system programmers and administrators for monitoring and managing processes efficiently. Here are the common process states:

- Running (R)

- The process is currently running or ready to run on a CPU core.

- It is actively executing instructions.

- The ps command may show this as R in the STAT column.

- Interruptible Sleep (S)

- The process is waiting for an event to occur.

- It is in a sleep state and can be woken up by signals.

- Commonly occurs when a process is waiting for I/O (like reading from disk or network).

- ps shows this as S in the STAT column.

- Uninterruptible Sleep (D)

- Similar to S, but the process cannot be interrupted by signals.

- Typically seen when a process is waiting for a resource that must be obtained (like disk I/O).

- It will not respond to signals until the operation completes.

- ps shows this as D in the STAT column.

- Zombie (Z)

- This state occurs when a child process has completed, but the parent process has not yet read its exit status.

- The process is dead but its entry remains in the process table.

- The kernel keeps this entry for the parent to read, allowing it to clean up resources.

- ps shows this as Z in the STAT column.

- Stopped (T)

- The process has been stopped, usually by receiving a SIGSTOP or SIGTSTP signal.

- It can be resumed later with SIGCONT.

- ps shows this as T in the STAT column.

- Paging (W)

- The process is swappable (can be moved to swap space).

- Rarely seen on modern systems.

- ps shows this as W in the STAT column.

- Traced or Stopped (t)

- The process is being traced by another process.

- ps shows this as t in the STAT column.

Also in man page of ps you can see:

PROCESS STATE CODES

Here are the different values that the s, stat and state output

specifiers (header "STAT" or "S") will display to describe the state of

a process:

D uninterruptible sleep (usually IO)

I Idle kernel thread

R running or runnable (on run queue)

S interruptible sleep (waiting for an event to complete)

T stopped by job control signal

t stopped by debugger during the tracing

W paging (not valid since the 2.6.xx kernel)

X dead (should never be seen)

Z defunct ("zombie") process, terminated but not reaped by

its parent

Source totozhang.github.io

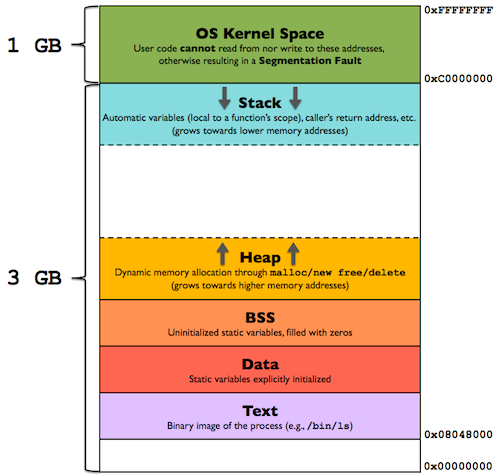

Memory Layout of a Process

The memory layout of a process in a Unix-like operating system, such as Linux, is typically divided into several segments, each serving a specific purpose. Understanding these memory segments is essential for system programmers, as it helps in understanding how memory is organized and utilized by processes.

Here are the common memory segments in the memory layout of a process:

The bottommost part of the process’s memory layout below the .text segment is typically unused and is often referred to as the “gap” or “gap space”. This area is intentionally left unused and serves as a guard region between the .text segment (where the executable code resides) and other segments like the stack and heap.

1. Text (Code) Segment The Text segment contains the executable machine instructions of the program. It is read-only and typically marked as non-writable and non-executable. This segment is shared among multiple instances of the same program (for efficiency) and is loaded from the executable file. When the program is executed, the CPU fetches instructions from this segment.

2. Data Segment The Data segment contains global and static variables used by the program. It is further divided into:

- Initialized Data: Initialized global and static variables (e.g., int x = 5;).

- Uninitialized Data (BSS): Uninitialized or zero-initialized global and static variables. The system initalizes all value’s of BSS segment to ‘0’. The data segment is writable but typically not executable. It is loaded into memory when the program starts.

3. Heap The Heap segment is dynamically allocated memory. It grows and shrinks during runtime as the program requests or releases memory using functions like malloc, calloc, realloc, and free. Memory in the heap is managed by the program and can be explicitly allocated and deallocated. Heap memory can become fragmented over time, leading to suboptimal memory usage.

4. Stack The Stack segment is used for function call management, local variables, and function call parameters. Each time a function is called, its local variables and parameters are pushed onto the stack. One stack frame is allocated for each function that are called. Hence, a frame stores the function’s local variables, function arguments. The stack grows and shrinks automatically as functions are called and return. Stack memory is faster to access than heap memory, as it is contiguous. Stack overflow can occur if the stack grows beyond its allocated size.

5. Environment Variables and command line arguments The Environment segment contains environment variables passed to the program. Environment variables are key-value pairs set by the shell or parent process. They provide information about the execution environment, such as PATH, HOME, etc. The env command or getenv() function can be used to access environment variables.

6. Memory Mapping Memory Mapping segments (or Virtual Memory Areas, VMAs) map files or devices into the process’s memory. They include memory-mapped files, shared libraries, and other mappings. mmap() system call is used to create memory mappings. Shared libraries (like libc.so) are loaded into memory as shared objects.

Refer: scaler

On Linux, you can access detailed information about a process’s memory layout through the /proc filesystem. For example:

/proc/<PID>/mapsprovides a list of memory mappings.- ` /proc/

/status` includes information about memory usage. /proc/<PID>/smapsgives detailed information about memory usage per mapping.

Each segment of the memory layout in C has its own read,write and executable permission. If a program tries to access the memory in a way that is not allowed, then a segmentation fault occurs.

Now the following code will clear everything.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

/* function declaration */

int addNum(int a, int b);

int iVar=10; // initialised - data segment

int uVar; // uninitialised - .bss segment

/* This code will be stored in .text segment as read only memory */

int main(){

int num1,num2,sum; // stack frame of 'main' function - stack segment

char *pstr; // pstr is part of stack frame of main()

char *buf = "welcome"; // "welcome" string is stored in .text segment, where as pointer to the string i.e buf is stored in stack frame of main()

char stackBuf[10] = "HelloWorld"; // stackBuf is stored on stack frame and it contains value "HelloWorld"

// buf[0]='A' // This will cause segmentation fault, as buf[0] tries to write to text segment, which is read only.

strcpy(stackBuf,"newStr"); // Possible as it is stored on stack

num1=10; // 10 is stored on stack

num2=20 // 20 is stored on stack

sum = addNum(num1,num2); // value of sum is stored on stack

}

Hence, now you will know the reason why once string declared by char *str we can’t change the content of the string.

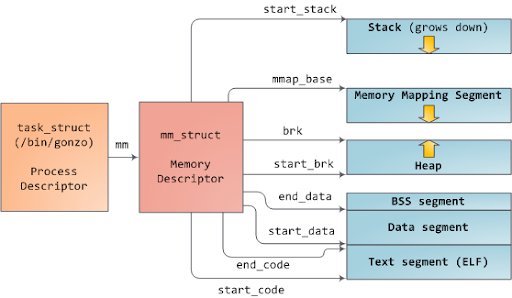

In Linux, each process has a unique virtual address space, which can be accessed through the mm_struct structure (aka “Memory Descriptor”). This structure contains details about the memory mappings for user space and kernel space. By reading this information, you can print the memory layout of a specific process.

Source manybutfinite.com